Ife-Benin: two kingdoms, one culture

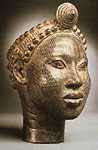

Considerng the central place it occupies in the general history of the Yoruba, we know surprisingly little about the history of Ife. After the comparative wealth of detail attached to the legendary founder of the State, Oduduwa, and his immediate successors, we encounter a very spare and broken narrative in the oral traditions for subsequent ages. The archaeological record had done something to fill the gaps, but this research is in its infancy. A first phase in the history of the State, opening around the eleventh century, is characterized by a scattered settlement pattern, the widespread use of floors made of potsherds set on edge, a glass-bead industry and a very fine terracotta art which specialized in the production of naturalistic figures, especially human heads. Because of this latter feature, a link has sometimes been posited between the cultures of the Ife and Nok, despite the thousand years which stands between them. More significant is the very close resemblance which the terracotta art of Ife beas to that discovered in other centres of Yoruba culture. Heads in a style related to that of Ife have been found ar Ikinrun and Ire near Oshogbo, at Idanre near Ikare, and most recently and interestingly at Owo, where a large number of terracotta sculptures have been excavated in a fifteenth-century context. This wide distribution of the style may indicate the extent of Ife influence, but it may also be that it marks the spread of a cultural trait among the Yoruba associated with religious rites rather than with Ife kingship. The potsherd floors, which in Ife have often been discovered in association with terracotta figures, are likewise not a unique feature of that city; similar floors have been found at Owo, Ifaki, Ikerin, Ede, Itaji Ekiti, Ikare and much futher afield at Ketu and Dassa Zoume in the Republic of Benin and in the Kabrais district of Togo. The earliest potsherd floors so far discovared in Ife date to about 1100 AD and the latest bear maize-cob impressions, which means that they cannot be earlier than the sisteenth century. The subsequent disappearance of the floors, and apparently also of the terracotta art, probably reflects some catastrophe which overwhelmed Ife in the sisteenth century. The twenty-five Ife "bronze" heads (they are in fact made of brass and copper), which bear so striking a stylistic resemblance to the terracottas, may have been made in the years immediately before the disaster, when imports of brass and copper by the Portuguese had made casting metal relatively plentiful. We can at present only surmise the nature of the events which distroyed this culture; conquest by an alien dynasty seems the most likely explanation. If the above interpretation of Ife history is correct, the dynasty which now reigns there is that which established itself in the sixteenth century, built the palace on its present site and threw up the ealiest of the walls around the central area of the town. Perhaps the new dynasty has preserved some of the political and social institutions of its predecessor, but we cannot assume that the earlier regime resembled the later in its political arrangements any more than it did in its art. Because the modern pattern of installation ceremonies and royal insignia are so similar throughout most of Yorubaland, including Ife, and because these insignia bear little resemblance to those worn by supposedly royal figures in the earlier phase of Ife history, it is reasonable to conclude that modern Yoruba kingship derives from the originally have been formed on the pattern of early Ife. It is not impossible that the rise and fall of State in the western Sudan in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had a direct influence on State fromation in the Guinea forest zone. Their appearance and expansion may well help to account for the upheavals which happened about that time in the adjacent southern States. We know that the Nupe drove the Yoruba from Old Oyo early in the sixteenth century, and that, before they returned to their capital three-quaters of a century later, the Oyo had reorganized their military forces so as to give greater prominence to the cavalry, the striking force of armies in the savannah States. From the Nupe the Oyo borrowed the Egungun cult of ancestors, and certain features of their revivified State may have come from the same source. Benin was the first State that the Portuguese visited on the coast; they soon established diplomatic as well as trade relations. Situated south-west of Ife, Benin probably became a kingdom early on, perhaps in the twelfth century. In the fifteenth century a major upheaval transformed this limited monarchy into an autocracy and the small State into a large kingdom. Tradition attributes the changes to a ruler known as Ewuare, who acquired the throne by outsting and killing a younger brother; in the course of the struggle much of the capital is said to have been destroyed. Ewuare rebuilt his capital to a new plan and gave it the name of Edo, which it has borne to this day. In the centre of the city a huge ditch and rampart were thrown up, cutting across older structures as did the city wall of Ife. Within the rampart a broad avenue separated the palace from the "town" --the quarters which housed numerous guilds of craftsmen and ritual specialists who served the ruler. The palace itself was organized into three departments--the wardrobe, the ruler's personal attendants and the harem--each with a staff graded into three ranks analogous to the age grades of the Edo villages. Archaeology has confirmed the traditions which assign the construction of the great wall of Ewuare and a major rebuilding of the palace to the fifteenth century. It has also shed light on the developments of the renowned Benin art of cire perdue (lost-wax) casting in brass and bronze. All brass objects found in a pre-sixteenth-century context prove to have been made by a smithing not a casting process. Although the cire perdue technique may have been known at an earlier date, it would seem, both from the archaeological evidence and from a stylistic study of the very large body of Benin brasswork still in existence, that only in the sixteenth century, with the import of large quantities of European brass, did this art become important. In general, wood sculpture dominates black African art. The Ife-Benin civilization is the brilliant exception, in that one finds works of art in terracotta and in bronze which accounts for the particular importance of this region in the general evolution of black African art. We noted earlier that objects in brass were either forged or made by the cire perdue technique, which was known at Ife probably earlier than the thirteenth century. In the light of the most recent research, a natural link unites the terracotta art illustrated by naturalistic figurines, particularly human heads, with the culture of Nok, which goes back to the Iron Age (the fifth century before the Christian era). This is most important and underlines the widespread diffusion of the Nok culture; moreover, we have evidence of exchanges and continuing contacts between the countries of the savannah and those of the forest to the south. Thus the well-known bronzes and naturalistic brass of Ife and Benin are the culmination of an artistic evolution begun at least as early as the Iron Age in a vast cultural region. This seems to be confirmed by the discovery in 1939, in the east of Nigeria, of the site of Igbo-Ukwu, which was explored in 1959 by Professor Thurstan Shaw; some 800 bronze pieces have been bought to light which are completely different from the Ife-Benin bronzes. Igbo-Ukwu is an urban complex in the middle of which were the palace and temples. Different buildings have been uncovered: a great room where plates and objects of worship and treasures were stored; a burial chamber of a great priest, richly decorated; and an enormous hole in which were deposited pottery, bones and other objects. Certainly there are some differences between the bronzes discovered at Igbo-Ukwu and the works of art of Ife. Nevertheless, a number of shared traits show that the two centres were part of the same culture. Indeed, we are in the presence, as at Ife, of a ritual monarchy. It is believed that Igbo-Ukwu was the religious capital of a very vast kingdom, and that the treasures were stored there under the keeping of a priest-king, Ezi Nzi. Information is lacking on the culture of Igbo-Ukwu; inquiries among those who guard oral tradition are continuing, and archaeologists see an extension of the area of bronze manufacture. Nevertheless, Igbo-Ukwu appears to contradict much of what has so far been postulated about State formation; on the evidence of radiocarbon dates, this highly sophisticated culture had evolved by the ninth century among Ibo peoples who otherwise maintained a "stateless" form of society. In other words, the Igbo-Ukwu culture antedates those of Ife and Benin, and all others of comparable complexity so far discovered in the forest region, by at least two centuries.

Considerng the central place it occupies in the general history of the Yoruba, we know surprisingly little about the history of Ife. After the comparative wealth of detail attached to the legendary founder of the State, Oduduwa, and his immediate successors, we encounter a very spare and broken narrative in the oral traditions for subsequent ages. The archaeological record had done something to fill the gaps, but this research is in its infancy. A first phase in the history of the State, opening around the eleventh century, is characterized by a scattered settlement pattern, the widespread use of floors made of potsherds set on edge, a glass-bead industry and a very fine terracotta art which specialized in the production of naturalistic figures, especially human heads. Because of this latter feature, a link has sometimes been posited between the cultures of the Ife and Nok, despite the thousand years which stands between them. More significant is the very close resemblance which the terracotta art of Ife beas to that discovered in other centres of Yoruba culture. Heads in a style related to that of Ife have been found ar Ikinrun and Ire near Oshogbo, at Idanre near Ikare, and most recently and interestingly at Owo, where a large number of terracotta sculptures have been excavated in a fifteenth-century context. This wide distribution of the style may indicate the extent of Ife influence, but it may also be that it marks the spread of a cultural trait among the Yoruba associated with religious rites rather than with Ife kingship. The potsherd floors, which in Ife have often been discovered in association with terracotta figures, are likewise not a unique feature of that city; similar floors have been found at Owo, Ifaki, Ikerin, Ede, Itaji Ekiti, Ikare and much futher afield at Ketu and Dassa Zoume in the Republic of Benin and in the Kabrais district of Togo. The earliest potsherd floors so far discovared in Ife date to about 1100 AD and the latest bear maize-cob impressions, which means that they cannot be earlier than the sisteenth century. The subsequent disappearance of the floors, and apparently also of the terracotta art, probably reflects some catastrophe which overwhelmed Ife in the sisteenth century. The twenty-five Ife "bronze" heads (they are in fact made of brass and copper), which bear so striking a stylistic resemblance to the terracottas, may have been made in the years immediately before the disaster, when imports of brass and copper by the Portuguese had made casting metal relatively plentiful. We can at present only surmise the nature of the events which distroyed this culture; conquest by an alien dynasty seems the most likely explanation. If the above interpretation of Ife history is correct, the dynasty which now reigns there is that which established itself in the sixteenth century, built the palace on its present site and threw up the ealiest of the walls around the central area of the town. Perhaps the new dynasty has preserved some of the political and social institutions of its predecessor, but we cannot assume that the earlier regime resembled the later in its political arrangements any more than it did in its art. Because the modern pattern of installation ceremonies and royal insignia are so similar throughout most of Yorubaland, including Ife, and because these insignia bear little resemblance to those worn by supposedly royal figures in the earlier phase of Ife history, it is reasonable to conclude that modern Yoruba kingship derives from the originally have been formed on the pattern of early Ife. It is not impossible that the rise and fall of State in the western Sudan in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had a direct influence on State fromation in the Guinea forest zone. Their appearance and expansion may well help to account for the upheavals which happened about that time in the adjacent southern States. We know that the Nupe drove the Yoruba from Old Oyo early in the sixteenth century, and that, before they returned to their capital three-quaters of a century later, the Oyo had reorganized their military forces so as to give greater prominence to the cavalry, the striking force of armies in the savannah States. From the Nupe the Oyo borrowed the Egungun cult of ancestors, and certain features of their revivified State may have come from the same source. Benin was the first State that the Portuguese visited on the coast; they soon established diplomatic as well as trade relations. Situated south-west of Ife, Benin probably became a kingdom early on, perhaps in the twelfth century. In the fifteenth century a major upheaval transformed this limited monarchy into an autocracy and the small State into a large kingdom. Tradition attributes the changes to a ruler known as Ewuare, who acquired the throne by outsting and killing a younger brother; in the course of the struggle much of the capital is said to have been destroyed. Ewuare rebuilt his capital to a new plan and gave it the name of Edo, which it has borne to this day. In the centre of the city a huge ditch and rampart were thrown up, cutting across older structures as did the city wall of Ife. Within the rampart a broad avenue separated the palace from the "town" --the quarters which housed numerous guilds of craftsmen and ritual specialists who served the ruler. The palace itself was organized into three departments--the wardrobe, the ruler's personal attendants and the harem--each with a staff graded into three ranks analogous to the age grades of the Edo villages. Archaeology has confirmed the traditions which assign the construction of the great wall of Ewuare and a major rebuilding of the palace to the fifteenth century. It has also shed light on the developments of the renowned Benin art of cire perdue (lost-wax) casting in brass and bronze. All brass objects found in a pre-sixteenth-century context prove to have been made by a smithing not a casting process. Although the cire perdue technique may have been known at an earlier date, it would seem, both from the archaeological evidence and from a stylistic study of the very large body of Benin brasswork still in existence, that only in the sixteenth century, with the import of large quantities of European brass, did this art become important. In general, wood sculpture dominates black African art. The Ife-Benin civilization is the brilliant exception, in that one finds works of art in terracotta and in bronze which accounts for the particular importance of this region in the general evolution of black African art. We noted earlier that objects in brass were either forged or made by the cire perdue technique, which was known at Ife probably earlier than the thirteenth century. In the light of the most recent research, a natural link unites the terracotta art illustrated by naturalistic figurines, particularly human heads, with the culture of Nok, which goes back to the Iron Age (the fifth century before the Christian era). This is most important and underlines the widespread diffusion of the Nok culture; moreover, we have evidence of exchanges and continuing contacts between the countries of the savannah and those of the forest to the south. Thus the well-known bronzes and naturalistic brass of Ife and Benin are the culmination of an artistic evolution begun at least as early as the Iron Age in a vast cultural region. This seems to be confirmed by the discovery in 1939, in the east of Nigeria, of the site of Igbo-Ukwu, which was explored in 1959 by Professor Thurstan Shaw; some 800 bronze pieces have been bought to light which are completely different from the Ife-Benin bronzes. Igbo-Ukwu is an urban complex in the middle of which were the palace and temples. Different buildings have been uncovered: a great room where plates and objects of worship and treasures were stored; a burial chamber of a great priest, richly decorated; and an enormous hole in which were deposited pottery, bones and other objects. Certainly there are some differences between the bronzes discovered at Igbo-Ukwu and the works of art of Ife. Nevertheless, a number of shared traits show that the two centres were part of the same culture. Indeed, we are in the presence, as at Ife, of a ritual monarchy. It is believed that Igbo-Ukwu was the religious capital of a very vast kingdom, and that the treasures were stored there under the keeping of a priest-king, Ezi Nzi. Information is lacking on the culture of Igbo-Ukwu; inquiries among those who guard oral tradition are continuing, and archaeologists see an extension of the area of bronze manufacture. Nevertheless, Igbo-Ukwu appears to contradict much of what has so far been postulated about State formation; on the evidence of radiocarbon dates, this highly sophisticated culture had evolved by the ninth century among Ibo peoples who otherwise maintained a "stateless" form of society. In other words, the Igbo-Ukwu culture antedates those of Ife and Benin, and all others of comparable complexity so far discovered in the forest region, by at least two centuries.

No comments:

Post a Comment