Map showing the greatest concentrations

of Yoruba around the globe

THE DEMOCRATIC FOUNDATIONS OF TRADITIONAL YORUBA GOVERNMENT

By डॉ Stephen Adebanji Akintoye

Most of the literature of European imperialism in

Africa characterized all traditional

African governments as autocratic and barbarously oppressive. The purpose of such

characterization was, of course, to justify the imposition of European rule on Africa, to

show that Europe was doing Africans the good service of bringing them “civilized”

government. The responses of Africans to all this will, naturally, vary from African

people to African people. In the case of the Yoruba people, the answer is that the

European characterization is not true of our traditional system of government. At bottom,

our political system rested on an acknowledgement of the sovereignty of the people, and

a respect by our rulers for their subjects. The practical consequence of this foundational

principle was that the Yoruba system vested in the people the right to choose their rulers

and the right to be consulted in the making of community decisions.

Throughout our remembered history, we Yorubas lived in small kingdoms which shared

the Yoruba homeland among them. In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, one of our

kingdoms, Oyo-ile, expanded its rule over many of the other kingdoms as well as over

territories of some of our non-Yoruba neighbors, and thus created a multi-kingdom

empire. That empire collapsed in the first years of the 19th century. Again in the second

half of the 19th century, another of our states, the city state of Ibadan, made a strong bid

to unify all of our kingdoms. It succeeded considerably, thus creating another multikingdom

empire for a few decades. Even at the height of the success of each of these

empire-building ventures, the small kingdoms continued to be the effective center of

political life of our people.

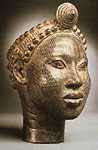

Each of these little kingdoms comprised a central town (or king’s town) and a number of

other towns and villages. The king or Oba, ruler of the whole kingdom, lived in the

king’s city in a large palace. His most important mark of kingship was the exalted beaded

crown which only he could wear. A subordinate ruler, called Baale, ruled each of the

subordinate towns and villages, and acknowledged the suzerainty of the king. Every town

was divided into quarters, each under a quarter chief. Each quarter was made up of many

large family compounds each of which housed many nuclear families (a nuclear family

being a man and his wife or wives and their children) all of whom claimed descent from

one ancestor. Ethnologists call the inhabitants of each family compound a “lineage”; in

this article, I will call them a “family group” – that is, a group consisting of many nuclear

families related by blood.

The family compound was where all our people lined, and it was the base of our

traditional system of government. Every family compound had its own internal

government. The Family Head was the leader of this compound government, assisted by

the elders. He was usually the oldest male member of the family group. All meetings of

www.YorubaNation.org 2

the family group were held under his chairmanship. The family group had a corporate

existence recognized by the whole society, corporate property rights, corporate duties,

corporate judicial authority – all of which necessitated frequent meetings. Giving girls in

marriage to other family groups and receiving girls as wives from other family groups

were corporate functions of each family group. The family group, exercising its judicial

authority, settled disputes within its nuclear families, between nuclear families, and

between individuals in the compound. The family group’s properties included, in the

town, its compound and the land on which it was built, and, beyond the town walls, its

farmland. Every member had the right to use parts of the group’s farmland, but no

member could sell or give any part of it away. Only the family group could allow a nonmember

to use parts of its land. The family group was very sensitive about its reputation

in the society, and therefore about its members’ conduct .and, for this reason, it exercised

beneficial authority over its members. It also bore much responsibility for the welfare of

its members and, therefore, had the power to mobilize contributions (in service or in

kind) from members in the interest of the whole group or of a needy member. Finally,

some family groups, in the course of the history of their town, became vested with

chieftaincy titles. At the death of the family group member who held such a title, the

family group meeting must choose his successor (even though his power as chief went

beyond the family compound); and the family group would then hand him over to the

king for the investiture.

The family group structure was the base on which our democratic system and traditions

were built. Inside the family compound, the family group meetings were strongly

democratic institutions. Every member had full rights and freedom to express his views.

In fact, it was one of the most important duties of the Family Head and the elders to

ensure, not only that every member’s opinion was heard, but also that every member was

encouraged to express opinion. Participating and contributing was regarded as every

member’s duty; and any member who habitually failed to honor that duty risked

becoming obnoxious in the compound. For the family group, moreover, continuity was a

matter of very great concern. The group conceived of itself as consisting not only of its

living members but also of its members who had already passed away, and those who

were yet to be born. The group buried its dead in the soil of its compound, and

systematically involved its children in its activities. The children were made to sit and

watch family group meetings. We Yorubas have a saying that a shrine which does not

regularly have children attend it rituals will perish. Women too – that is, wives of

members (or Obirin Ile) – commanded great influence in the affairs of the compound. No

compound would take a decision without involving its women. And, in such matters as

weddings and engagements, the women were very influential indeed.

Early foreign visitors to Yorubaland (for instance the Christian missionaries in the 19th

century), were often impressed by how eloquently and fearlessly Yoruba people could

express themselves in meetings and gatherings. The culture of the family group

compound was the school where the eloquence and confidence of expression were

inculcated.

In the context of the wider society of a town or village, the individual’s membership of a

family group was all-important. It guaranteed for him protection against abuse and

www.YorubaNation.org 3

disrespect. A citizen who abused or grossly disrespected another citizen risked conflict

between his own family group and that of the victim. In the exercise of their powers and

judicial authority in their quarters, quarter chiefs were supposed to consult the leaders of

the family compounds regularly. Even at the highest levels of government, in the palace,

leaders of the family compounds were treated as a very important level of authority.

Before trying and punishing an offender, for instance, the palace would usually contact

and consult the leader of his compound.

The title of king was hereditary in the royal family group. So too were the titles of Baale

and quarter chiefs in their own particular family groups. In the appointment of a king, the

Yoruba political system took a decidedly democratic direction. In other known

monarchical systems worldwide, the king is simply succeeded by his eldest child. This

system of succession, known as primogeniture, was completely rejected by the Yoruba

people, even though it was the system used by our closest neighbors - for instance, the

Edo kingdom of Benin. When a Yoruba king died, he was not automatically succeeded

by his son. All male members of the royal family group, sons (and even grandsons) of

former kings, were eligible for selection as king. In some kingdoms, the oldest son of the

recently deceased king was ineligible; in some others, all his sons were ineligible.

This system of selection meant that a Yoruba king was not only born, but was also

selected by his subjects from a pool of eligible princes. Unlike other monarchical

systems. we chose our kings – an acknowledgment that ultimate power belonged to the

people.

The power to carry out the selection on behalf of the people was vested in a standing

committee of chiefs now known as the Council of Kingmakers. The selection by this

council was always final. In theory, the Council of Kingmakers was all-powerful in this

matter of selecting a king, but in reality its powers were limited by many circumstances.

First, the general populace was free to lobby the kingmakers individually and collectively

and to express opinions on the princes, and the kingmakers were obliged to listen to the

people and seriously consider their opinions and wishes. Consequently, as the

remembered history of any of our kingdoms will reveal, decisions of the kingmakers

were frequently expressions of the people’s wishes. When, at the end of the exercise, the

Council of Kingmakers told the people, “We have given you your king. We have done

what you asked us to do”, they were speaking the truth. The selection was essentially a

decision of the people.

Secondly, neither the chiefs nor the common people ever wanted to give the palace to

some rich or powerful prince who could later claim that he won the throne on the strength

of his wealth or power. Ours was a sort of “limited monarchy”, and the ideal candidate

was a prince who was assessed to be temperamentally able to work within the traditional

limitations on royal power. The history of every Yoruba kingdom is replete with stories

of rich, powerful, princes who were passed over for their humbler brothers or cousins.

The chiefs and people were usually generally agreed on this, even though most eligible

princes would have partisan supporters of their own.

www.YorubaNation.org 4

In the important matter of selecting our rulers, the young state of Ibadan, newly founded

in the 19th century, went even more democratic than the national norm. Ibadan turned its

back on the hereditary principle; instead, it instituted a system of total selection. Anybody

who demonstrated leadership abilities and good character, no matter his origin, could be

appointed a chief. The new comer to position of leadership would be started with a junior

chieftaincy title; he would then be promoted step by step up the line as vacancies

occurred. His continued retention on the promotional ranks depended entirely on his

performance and continued good character. With luck (if enough chiefs ahead of him fell

off or died), he could rise to the very top. It was a system of meritocracy. Under this

system, Ibadan set up two parallel chieftaincy lines – a civil line and a military line. The

head of the civil line was the Baale (now the Olubadan), and the head of the military line

was the Bashorun (although the greatest of the Ibadan generals, Latoosa, preferred the

title of Aare when he rose to the top). The Ibadan masses exercised very powerful

influence over the selection and promotion of their chiefs. Massive public demonstrations

were an important feature of Ibadan’s political life.

Even in the more conservative, older, kingdoms, the powers of a king were limited. In

theory, the government was the king’s, and he was spoken of as having the power of life

and death over his subjects. We called our kings “Ekeji orisha” (lieutenant of the gods),

and said that the king owned all the land – “Oba l’o ni ile”. In practice, however, there

was not much truth in all these. The king must rule with established councils of chiefs,

the highest of which councils met with the king daily in the palace to take all decisions

and to function as the highest court of appeal. After its decisions were taken, they were

announced as the king’s decisions. Then the town crier would go through the streets

proclaiming, “The king greets you all and says so and so and so”, and the people would

loudly respond from their homes, “May the king’s will be done”.

Over land, the king’s authority was very small indeed. Within the town, the king’s

government simply could not touch a family group’s compound for any purpose. Beyond

the town walls, the king could not do anything to a family group’s farmland without the

explicit consent of the family group. “Oba l’o ni ile” therefore meant no more than that

the king was protector of all the land, and that he was the adjudicator when land was in

dispute between family groups.

Every kingdom had an annual festival or two during which the common people were

totally free to demonstrate in the streets and say whatever they chose to say, usually in

crudely composed songs, about their king and chiefs. No holds barred; no complaints; no

arrests! This was a way of reminding the persons in authority that the authority belonged

to the people.

Most kingdoms also had institutionalized town meetings in the palace at which any

citizen could express opinion or offer suggestion about current events and ask questions

from the chiefs. Such meetings were held from time to time throughout the year, usually

early in the morning of certain market days traditionally known to all citizens as town

meeting days.

www.YorubaNation.org 5

We did not only establish the right to select our kings, we also established the right to

remove them. If a king became over-ambitious and tried to establish personal power

beyond the limited monarchy system, or if he became tyrannical, greedy, or otherwise

seriously unpopular, some chiefs bore the constitutional duty of cautioning, counseling,

rebuking him in private. If he would not mend his ways, the chiefs might take his matter

before a special council of notables and elders called Ogboni where he would be

seriously warned. If he still would not change, the quarter chiefs might alert the Family

Heads - and the latter might inform their compound meetings. The final action would

then be that certain chiefs, whose traditional duty it was to do it, would approach the king

and respectfully ask him to “go to sleep”, that is, commit suicide – and he would do so. A

Yoruba king could never leave the throne and live as an ordinary citizen. This final action

against a king was very rarely taken, but every king was informed at the time of his

installation that it was in the power of his subjects.

Our traditional constitution created very important roles for our women. In every one of

our kingdoms, towns and villages, we had a cadre of women chiefs, the highest ranking

of whom was part of the highest council of chiefs. There were also specialized women’s

chieftaincy titles whose holders performed special duties in the society. And, though our

laws generally excluded women from being kings, only a woman (a princess) could be

appointed as regent between the death of a king and the appointment and installation of

his successor. Our women were among the greatest traders in Africa, and they enjoyed

freedom to travel throughout the length and breadth of our homeland and beyond, buying

and selling. In most Yoruba communities, there were women who were very wealthy in

their own right. According to the written records available to us, for instance, two of the

richest and politically most influential people in our country in the 19th century (before

British rule), were women – namely, the Iyalode Efunseetan of Ibadan, and Madam

Tinubu of Lagos. Both were great traders. In addition, the Iyalode had a large farming

business in which there were employed at one time, according to the records of the

missionaries who knew her, over 2000 workers.

Finally, the king’s relationship with the Baale in his kingdom was never one of detailed

control or coercion. It subsisted on mutual benefits. As defender of the kingdom, the king

could ask the Baale for contribution of men and materials if any part of the kingdom was

attacked. That benefited all towns and villages. Besides that, the Baale honored the king

with gifts on certain ceremonies, and contributed men and materials to the occasional

repairs on the palace buildings. In return, the Baale was free to send to the king difficult

disputes that arose in his town or village. Rigid taxes and levies did not form part of the

system. In the day-to-day governance of his town or village, the Baale was not controlled

by the king. Residents of the subordinate towns and villages usually had no reason to feel

inferior to the residents of the king’s town.

Raised in this culture of democracy, we Yoruba people cherished our individual freedom

and independence. We were not used to being repressed or degraded by our rulers. Even

when we found ourselves in the naturally restrictive, authoritarian, setting of a war camp,

we still preserved our freedom and our right to participate in decisions that affected our

society. For instance in 1886, the British government sent some men to come to the war

www.YorubaNation.org 6

camps between Igbajo and Imesi-ile and offer to help make peace between an Ibadan

army and the Ekitiparapo army facing each other there. In its bid to unify all of

Yorubaland, Ibadan had conquered most of the Yoruba kingdoms. In 1877, the kingdoms

of the Ekiti, Ijesha, Igbomina and Akoko had formed a confederacy, named Ekitiparapo,

to resist Ibadan. Chief Ogedemgbe of Ilesha was the Commander-in-chief of the

Ekitiparapo army. When the British officials came to the Ekitiparapo camp, they, in

between official meetings with Ogedemgbe and his officers, walked around the camp

talking with the soldiers. In one such conversation with a group of soldiers, one soldier

told the foreigners that it was the joint decision of all members of the Ekitiparapo to stay

firm where they were until the Ibadan army had gone away. If Ogedemgbe were to try to

move without a change of that decision by all, he added, “We will cut off his head”. How

surprised the visitors must have been by such freedom of speech!

In short, our forefathers evolved a political culture that was democratic. Political contests,

chieftaincy disputes, group rivalries, open discussion of issues, popular protests – all

these have been common in our political life from very early times.

This freedom and independence is, needless to say, strength. In an autonomous modern

Yorba country, it would have produced a vibrantly democratic and progressive society. In

a Nigeria of many peoples, however, it has looked like weakness and, on many critical

occasions, it has even operated as outright weakness. Used to freedom of opinion and

choice, the Yorubas have, in Nigeria, been the most accommodating of ideas and political

parties and have appeared, unlike other peoples, incapable of sticking together even when

their vital interests have been obviously in jeopardy. A friendly, non-Yoruba politician in

the 1960s Chief Tony Enahoro, expressed his dismay at this apparent factiousness of the

Yoruba people in the following words: “Political rivalry has always been most keen, even

bitter, in the Western Region. This is partly because party politics is more advanced there

than in the rest of the country, the people having been accustomed by their long history of

chieftaincy disputes to the political game of “ins” and “outs”; partly because a higher

standard of living from less exacting labor affords them comparatively more time for

public affairs; partly because the Yorubas, in politics as in religion, prefer to worship

many gods - - -“.

Our apparent proneness towards divisions and factiousness are products of our history of

political democracy. Because of our democratic orientation too, we respect our right to

choose, and have usually, in Nigerian politics, reacted very violently when politicians

dare to insult us by rigging our votes at elections. Finally, a democratically oriented

society tends to attach much importance and priority to education. This, therefore, is the

reason why we as a people are the crusaders for education in Nigeria, why we were the

first African people to institute a free education program, and why we are the most

literate people today on the African continent.

African governments as autocratic and barbarously oppressive. The purpose of such

characterization was, of course, to justify the imposition of European rule on Africa, to

show that Europe was doing Africans the good service of bringing them “civilized”

government. The responses of Africans to all this will, naturally, vary from African

people to African people. In the case of the Yoruba people, the answer is that the

European characterization is not true of our traditional system of government. At bottom,

our political system rested on an acknowledgement of the sovereignty of the people, and

a respect by our rulers for their subjects. The practical consequence of this foundational

principle was that the Yoruba system vested in the people the right to choose their rulers

and the right to be consulted in the making of community decisions.

Throughout our remembered history, we Yorubas lived in small kingdoms which shared

the Yoruba homeland among them. In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, one of our

kingdoms, Oyo-ile, expanded its rule over many of the other kingdoms as well as over

territories of some of our non-Yoruba neighbors, and thus created a multi-kingdom

empire. That empire collapsed in the first years of the 19th century. Again in the second

half of the 19th century, another of our states, the city state of Ibadan, made a strong bid

to unify all of our kingdoms. It succeeded considerably, thus creating another multikingdom

empire for a few decades. Even at the height of the success of each of these

empire-building ventures, the small kingdoms continued to be the effective center of

political life of our people.

Each of these little kingdoms comprised a central town (or king’s town) and a number of

other towns and villages. The king or Oba, ruler of the whole kingdom, lived in the

king’s city in a large palace. His most important mark of kingship was the exalted beaded

crown which only he could wear. A subordinate ruler, called Baale, ruled each of the

subordinate towns and villages, and acknowledged the suzerainty of the king. Every town

was divided into quarters, each under a quarter chief. Each quarter was made up of many

large family compounds each of which housed many nuclear families (a nuclear family

being a man and his wife or wives and their children) all of whom claimed descent from

one ancestor. Ethnologists call the inhabitants of each family compound a “lineage”; in

this article, I will call them a “family group” – that is, a group consisting of many nuclear

families related by blood.

The family compound was where all our people lined, and it was the base of our

traditional system of government. Every family compound had its own internal

government. The Family Head was the leader of this compound government, assisted by

the elders. He was usually the oldest male member of the family group. All meetings of

www.YorubaNation.org 2

the family group were held under his chairmanship. The family group had a corporate

existence recognized by the whole society, corporate property rights, corporate duties,

corporate judicial authority – all of which necessitated frequent meetings. Giving girls in

marriage to other family groups and receiving girls as wives from other family groups

were corporate functions of each family group. The family group, exercising its judicial

authority, settled disputes within its nuclear families, between nuclear families, and

between individuals in the compound. The family group’s properties included, in the

town, its compound and the land on which it was built, and, beyond the town walls, its

farmland. Every member had the right to use parts of the group’s farmland, but no

member could sell or give any part of it away. Only the family group could allow a nonmember

to use parts of its land. The family group was very sensitive about its reputation

in the society, and therefore about its members’ conduct .and, for this reason, it exercised

beneficial authority over its members. It also bore much responsibility for the welfare of

its members and, therefore, had the power to mobilize contributions (in service or in

kind) from members in the interest of the whole group or of a needy member. Finally,

some family groups, in the course of the history of their town, became vested with

chieftaincy titles. At the death of the family group member who held such a title, the

family group meeting must choose his successor (even though his power as chief went

beyond the family compound); and the family group would then hand him over to the

king for the investiture.

The family group structure was the base on which our democratic system and traditions

were built. Inside the family compound, the family group meetings were strongly

democratic institutions. Every member had full rights and freedom to express his views.

In fact, it was one of the most important duties of the Family Head and the elders to

ensure, not only that every member’s opinion was heard, but also that every member was

encouraged to express opinion. Participating and contributing was regarded as every

member’s duty; and any member who habitually failed to honor that duty risked

becoming obnoxious in the compound. For the family group, moreover, continuity was a

matter of very great concern. The group conceived of itself as consisting not only of its

living members but also of its members who had already passed away, and those who

were yet to be born. The group buried its dead in the soil of its compound, and

systematically involved its children in its activities. The children were made to sit and

watch family group meetings. We Yorubas have a saying that a shrine which does not

regularly have children attend it rituals will perish. Women too – that is, wives of

members (or Obirin Ile) – commanded great influence in the affairs of the compound. No

compound would take a decision without involving its women. And, in such matters as

weddings and engagements, the women were very influential indeed.

Early foreign visitors to Yorubaland (for instance the Christian missionaries in the 19th

century), were often impressed by how eloquently and fearlessly Yoruba people could

express themselves in meetings and gatherings. The culture of the family group

compound was the school where the eloquence and confidence of expression were

inculcated.

In the context of the wider society of a town or village, the individual’s membership of a

family group was all-important. It guaranteed for him protection against abuse and

www.YorubaNation.org 3

disrespect. A citizen who abused or grossly disrespected another citizen risked conflict

between his own family group and that of the victim. In the exercise of their powers and

judicial authority in their quarters, quarter chiefs were supposed to consult the leaders of

the family compounds regularly. Even at the highest levels of government, in the palace,

leaders of the family compounds were treated as a very important level of authority.

Before trying and punishing an offender, for instance, the palace would usually contact

and consult the leader of his compound.

The title of king was hereditary in the royal family group. So too were the titles of Baale

and quarter chiefs in their own particular family groups. In the appointment of a king, the

Yoruba political system took a decidedly democratic direction. In other known

monarchical systems worldwide, the king is simply succeeded by his eldest child. This

system of succession, known as primogeniture, was completely rejected by the Yoruba

people, even though it was the system used by our closest neighbors - for instance, the

Edo kingdom of Benin. When a Yoruba king died, he was not automatically succeeded

by his son. All male members of the royal family group, sons (and even grandsons) of

former kings, were eligible for selection as king. In some kingdoms, the oldest son of the

recently deceased king was ineligible; in some others, all his sons were ineligible.

This system of selection meant that a Yoruba king was not only born, but was also

selected by his subjects from a pool of eligible princes. Unlike other monarchical

systems. we chose our kings – an acknowledgment that ultimate power belonged to the

people.

The power to carry out the selection on behalf of the people was vested in a standing

committee of chiefs now known as the Council of Kingmakers. The selection by this

council was always final. In theory, the Council of Kingmakers was all-powerful in this

matter of selecting a king, but in reality its powers were limited by many circumstances.

First, the general populace was free to lobby the kingmakers individually and collectively

and to express opinions on the princes, and the kingmakers were obliged to listen to the

people and seriously consider their opinions and wishes. Consequently, as the

remembered history of any of our kingdoms will reveal, decisions of the kingmakers

were frequently expressions of the people’s wishes. When, at the end of the exercise, the

Council of Kingmakers told the people, “We have given you your king. We have done

what you asked us to do”, they were speaking the truth. The selection was essentially a

decision of the people.

Secondly, neither the chiefs nor the common people ever wanted to give the palace to

some rich or powerful prince who could later claim that he won the throne on the strength

of his wealth or power. Ours was a sort of “limited monarchy”, and the ideal candidate

was a prince who was assessed to be temperamentally able to work within the traditional

limitations on royal power. The history of every Yoruba kingdom is replete with stories

of rich, powerful, princes who were passed over for their humbler brothers or cousins.

The chiefs and people were usually generally agreed on this, even though most eligible

princes would have partisan supporters of their own.

www.YorubaNation.org 4

In the important matter of selecting our rulers, the young state of Ibadan, newly founded

in the 19th century, went even more democratic than the national norm. Ibadan turned its

back on the hereditary principle; instead, it instituted a system of total selection. Anybody

who demonstrated leadership abilities and good character, no matter his origin, could be

appointed a chief. The new comer to position of leadership would be started with a junior

chieftaincy title; he would then be promoted step by step up the line as vacancies

occurred. His continued retention on the promotional ranks depended entirely on his

performance and continued good character. With luck (if enough chiefs ahead of him fell

off or died), he could rise to the very top. It was a system of meritocracy. Under this

system, Ibadan set up two parallel chieftaincy lines – a civil line and a military line. The

head of the civil line was the Baale (now the Olubadan), and the head of the military line

was the Bashorun (although the greatest of the Ibadan generals, Latoosa, preferred the

title of Aare when he rose to the top). The Ibadan masses exercised very powerful

influence over the selection and promotion of their chiefs. Massive public demonstrations

were an important feature of Ibadan’s political life.

Even in the more conservative, older, kingdoms, the powers of a king were limited. In

theory, the government was the king’s, and he was spoken of as having the power of life

and death over his subjects. We called our kings “Ekeji orisha” (lieutenant of the gods),

and said that the king owned all the land – “Oba l’o ni ile”. In practice, however, there

was not much truth in all these. The king must rule with established councils of chiefs,

the highest of which councils met with the king daily in the palace to take all decisions

and to function as the highest court of appeal. After its decisions were taken, they were

announced as the king’s decisions. Then the town crier would go through the streets

proclaiming, “The king greets you all and says so and so and so”, and the people would

loudly respond from their homes, “May the king’s will be done”.

Over land, the king’s authority was very small indeed. Within the town, the king’s

government simply could not touch a family group’s compound for any purpose. Beyond

the town walls, the king could not do anything to a family group’s farmland without the

explicit consent of the family group. “Oba l’o ni ile” therefore meant no more than that

the king was protector of all the land, and that he was the adjudicator when land was in

dispute between family groups.

Every kingdom had an annual festival or two during which the common people were

totally free to demonstrate in the streets and say whatever they chose to say, usually in

crudely composed songs, about their king and chiefs. No holds barred; no complaints; no

arrests! This was a way of reminding the persons in authority that the authority belonged

to the people.

Most kingdoms also had institutionalized town meetings in the palace at which any

citizen could express opinion or offer suggestion about current events and ask questions

from the chiefs. Such meetings were held from time to time throughout the year, usually

early in the morning of certain market days traditionally known to all citizens as town

meeting days.

www.YorubaNation.org 5

We did not only establish the right to select our kings, we also established the right to

remove them. If a king became over-ambitious and tried to establish personal power

beyond the limited monarchy system, or if he became tyrannical, greedy, or otherwise

seriously unpopular, some chiefs bore the constitutional duty of cautioning, counseling,

rebuking him in private. If he would not mend his ways, the chiefs might take his matter

before a special council of notables and elders called Ogboni where he would be

seriously warned. If he still would not change, the quarter chiefs might alert the Family

Heads - and the latter might inform their compound meetings. The final action would

then be that certain chiefs, whose traditional duty it was to do it, would approach the king

and respectfully ask him to “go to sleep”, that is, commit suicide – and he would do so. A

Yoruba king could never leave the throne and live as an ordinary citizen. This final action

against a king was very rarely taken, but every king was informed at the time of his

installation that it was in the power of his subjects.

Our traditional constitution created very important roles for our women. In every one of

our kingdoms, towns and villages, we had a cadre of women chiefs, the highest ranking

of whom was part of the highest council of chiefs. There were also specialized women’s

chieftaincy titles whose holders performed special duties in the society. And, though our

laws generally excluded women from being kings, only a woman (a princess) could be

appointed as regent between the death of a king and the appointment and installation of

his successor. Our women were among the greatest traders in Africa, and they enjoyed

freedom to travel throughout the length and breadth of our homeland and beyond, buying

and selling. In most Yoruba communities, there were women who were very wealthy in

their own right. According to the written records available to us, for instance, two of the

richest and politically most influential people in our country in the 19th century (before

British rule), were women – namely, the Iyalode Efunseetan of Ibadan, and Madam

Tinubu of Lagos. Both were great traders. In addition, the Iyalode had a large farming

business in which there were employed at one time, according to the records of the

missionaries who knew her, over 2000 workers.

Finally, the king’s relationship with the Baale in his kingdom was never one of detailed

control or coercion. It subsisted on mutual benefits. As defender of the kingdom, the king

could ask the Baale for contribution of men and materials if any part of the kingdom was

attacked. That benefited all towns and villages. Besides that, the Baale honored the king

with gifts on certain ceremonies, and contributed men and materials to the occasional

repairs on the palace buildings. In return, the Baale was free to send to the king difficult

disputes that arose in his town or village. Rigid taxes and levies did not form part of the

system. In the day-to-day governance of his town or village, the Baale was not controlled

by the king. Residents of the subordinate towns and villages usually had no reason to feel

inferior to the residents of the king’s town.

Raised in this culture of democracy, we Yoruba people cherished our individual freedom

and independence. We were not used to being repressed or degraded by our rulers. Even

when we found ourselves in the naturally restrictive, authoritarian, setting of a war camp,

we still preserved our freedom and our right to participate in decisions that affected our

society. For instance in 1886, the British government sent some men to come to the war

www.YorubaNation.org 6

camps between Igbajo and Imesi-ile and offer to help make peace between an Ibadan

army and the Ekitiparapo army facing each other there. In its bid to unify all of

Yorubaland, Ibadan had conquered most of the Yoruba kingdoms. In 1877, the kingdoms

of the Ekiti, Ijesha, Igbomina and Akoko had formed a confederacy, named Ekitiparapo,

to resist Ibadan. Chief Ogedemgbe of Ilesha was the Commander-in-chief of the

Ekitiparapo army. When the British officials came to the Ekitiparapo camp, they, in

between official meetings with Ogedemgbe and his officers, walked around the camp

talking with the soldiers. In one such conversation with a group of soldiers, one soldier

told the foreigners that it was the joint decision of all members of the Ekitiparapo to stay

firm where they were until the Ibadan army had gone away. If Ogedemgbe were to try to

move without a change of that decision by all, he added, “We will cut off his head”. How

surprised the visitors must have been by such freedom of speech!

In short, our forefathers evolved a political culture that was democratic. Political contests,

chieftaincy disputes, group rivalries, open discussion of issues, popular protests – all

these have been common in our political life from very early times.

This freedom and independence is, needless to say, strength. In an autonomous modern

Yorba country, it would have produced a vibrantly democratic and progressive society. In

a Nigeria of many peoples, however, it has looked like weakness and, on many critical

occasions, it has even operated as outright weakness. Used to freedom of opinion and

choice, the Yorubas have, in Nigeria, been the most accommodating of ideas and political

parties and have appeared, unlike other peoples, incapable of sticking together even when

their vital interests have been obviously in jeopardy. A friendly, non-Yoruba politician in

the 1960s Chief Tony Enahoro, expressed his dismay at this apparent factiousness of the

Yoruba people in the following words: “Political rivalry has always been most keen, even

bitter, in the Western Region. This is partly because party politics is more advanced there

than in the rest of the country, the people having been accustomed by their long history of

chieftaincy disputes to the political game of “ins” and “outs”; partly because a higher

standard of living from less exacting labor affords them comparatively more time for

public affairs; partly because the Yorubas, in politics as in religion, prefer to worship

many gods - - -“.

Our apparent proneness towards divisions and factiousness are products of our history of

political democracy. Because of our democratic orientation too, we respect our right to

choose, and have usually, in Nigerian politics, reacted very violently when politicians

dare to insult us by rigging our votes at elections. Finally, a democratically oriented

society tends to attach much importance and priority to education. This, therefore, is the

reason why we as a people are the crusaders for education in Nigeria, why we were the

first African people to institute a free education program, and why we are the most

literate people today on the African continent.

No comments:

Post a Comment